I set a challenge for myself to read 26 books in 2017—one every two weeks. I actually managed to read 27 this year, and perhaps even 28 if I finish Chip and Dan Heath’s Decisive before midnight tonight. This is no doubt the result of handing in my dissertation and finishing grad school, but my reading life was also invigorated by joining Book of the Month (BOTM). Half of my favorites for the year came to me as my monthly selections or optional add-ons. Although I read some great non-fiction and memoirs, I gravitated towards fiction—again, indubitably a reaction to the past three years of almost-total immersion in history books.

In reviewing my list of top picks, I noticed a few themes running throughout these ten books. Three of my favorite works of fiction were written by Asian-American or black authors, and offered commentary on the experience of immigration, heritage, and belonging/otherness in American and “native” cultures. Three books, interestingly, focused on adoption as a way to examine this latter theme. Unsurprisingly, considering the political events of 2017, both the fiction and non-fiction books I read concerned themselves with justice—how it is circumvented, contested, delivered, and measured. Finally, I read several books this year that I loved for their keen observations of the world and of the eccentric people who populate it.

Although the majority of these books were published in 2017, I have chosen this selection from the books I read this year regardless of their publication date. I have also included a few honorable mentions and two extra lists from some of my favorite readers (read to the end for the top ten picks in Children’s and Young Adult fiction by my husband, a fourth grade teacher, and the top ten of my friend Amanda Katz, herself a voracious reader).

10. John Boyne, The Heart’s Invisible Furies (BOTM, August Selection)

I loved the first half of this massive novel about an adopted boy (Cyril Avery) who falls in love with his best friend (Julian) and spends most of his young-adulthood in the 1960s and 1970s coming to grips with his sexuality and his rejection by his friend, his family, and his country. It’s a bildungsroman, and I tore through the chapters about Cyril’s birth mother, his adoption and unconventional childhood, and his move to Amsterdam—a city more tolerant of gay love than repressive Dublin. I never quite warmed to the adult Cyril, however; although I found the evolution of his character believable, I no longer cared to read about him.

9. James B. Stewart, Tangled Webs: How False Statements are Undermining America: From Martha Stewart to Bernie Madoff (McKay’s Books, Nashville)

I found a used copy of Tangled Webs on a shelf at McKay’s Books in Nashville in February, and because it’s a few years old now (published in 2011) it only cost a few bucks. The topic of lying under oath felt pretty relevant in February, and feels even more so now. "To elevate loyalty over truth,” Stewart presciently wrote, “is to revert to the rule of the tribe or clan, where power and brute force decide all conflicts." Stewart focuses on four case studies of prominent Americans who lied under oath and were convicted of perjury: Martha Stewart, Scooter Libby, Barry Bonds, and Bernie Madoff. I am constantly reminded of the book when I watch the news, particularly the Libby chapter (though I found the Martha Stewart and Bernie Madoff chapters to be the most enjoyable to read). These four cases were brought to justice, now let’s hope we see more indictments as a result of Mueller’s investigation.

8. David Sedaris, Theft By Finding: Diaries 1977-2002 (BOTM, June Extra Selection)

I have seen David Sedaris read twice—I have a signed copy of Me Talk Pretty!—and both times he concluded by reading excerpts from his journal, and both times I nearly peed in my pants from laughing so hard. Sedaris is so perceptive of quotidian eccentricities, those things that we notice in passing but don’t bother to analyze beyond a shrug and a shake of the head. I haven’t been able to look at an IHOP without laughing since reading this book.

Yes, with my name spelled incorrectly.

7. Holly Tucker, City of Light, City of Poison: Murder, Magic, and the First Police Chief of Paris (Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh)

I interviewed Tucker about City of Light, City of Poison for the “Disciplining the City” series on the Urban History Association’s blog, The Metropole (which I co-edit). I knew nothing about seventeenth-century France before picking up the book. In reading about the “affair of the poisons,” a scandal amongst the French nobility that was uncovered by Paris’s chief of police, I recognized many parallels between policing and the justice system in seventeenth-century France and twentieth- and twenty-first century America. In both past and present the application of “justice” reflects society’s distrust of “others,” including women and the poor, often resulting in overzealous prosecution and wrongful convictions.

6. David Grann, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI (BOTM, August Extra Selection)

Grann’s book is a brilliant example of how to write fully-realized, complicated history for a popular audience. Killers of the Flower Moon is a journalistic accounting of the theft of the Osage Indian Nation’s oil wealth by white Oklahomans during the 1920s and 1930s. Grann spools out this story with great suspense, but never misses a chance to condemn the greedy, exploitative, traitorous white “friends” and neighbors of the Osage Nation nor the “justice” system that failed to protect the Osage and prosecute their killers.

5. Nathan Hill, The Nix (Gift from Judi Seal, purchased at The Ivy Bookshop, Baltimore)

I read The Nix the week after handing in my dissertation, and so I really got the full immersive, escapist experience this book demands and provides. As an urban historian specializing in postwar America, The Nix was catnip for me. The plot is pretty complicated, to the point where I will not even attempt a one-line summary, but half of the book takes place in Chicago in 1968 during the riots at the Democratic National Convention. The rest takes place in the present, when the protagonist is working as an English professor at a small college outside of Chicago. I am not exaggerating when I say that Part I, Chapter 4—the argument between the professor and his student, Laura Pottsdam, who has plagiarized a paper—is one of the greatest pieces of writing that I have ever encountered.

4. Victor LaValle, The Changeling (The Ivy Bookshop, Baltimore)

I picked up this novel on my birthday, on the recommendation of one of The Metropole’s Members of the Week, Elizabeth Todd-Breland. She wrote of The Changeling that “It is a beautiful and thrilling novel that challenged me to be more imaginative in thinking about the space and genre of the city in the particular way that good fiction can.” I could not agree more with her assessment. Set in New York City, this modern-day fairy tale is a fantastic adventure love story about Apollo Kagwa, whose wife Emma Valentine and son Brian disappear after a series of mysterious events. LaValle weaves commentary about present evils into the warp and weft of his fictional evildoers, particularly racism, misogyny, and the oversharing culture of the Internet and social media. A creepy and clever read!

3. Lisa Ko, The Leavers (BOTM, May Selection)

Ko’s debut novel is a modern immigration story and an examination of foreign/interracial adoption. The protagonists are Polly and Deming Guo, a mother and son; after Polly fails to come home one day, Deming is adopted by a childless white couple and renamed Daniel. Although the liberal Wilkensons attempt to connect Deming/Daniel with his heritage, he is left with question about his mother and his past. Ko’s story follows Deming/Daniel’s search for answers, allowing her to explore questions such as: who defines you as a child? can you be “from” somewhere as a young immigrant, or are you always different or “between” places? can adoptive parents succeed in connecting their children to their heritage? I could not put this book down, and loved the experience of reading it, but I have also been surprised by how it has stayed with me and how often I think about the themes and questions it raises.

2. William Finnegan, Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life (Parnassus Books, Nashville)

Who knew I loved surfing? I had no interest in the sport before picking up Finnegan’s memoir, but I had heard rave reviews of the book. It did not disappoint. Like a strong undertow, Finnegan’s descriptions of waves, boards, buddies, family, cities, and travels completely sucked me in to his life and into the sport of surfing. For a while, my YouTube suggestions were all surf videos, because I would search for the waves he described surfing so that I could better understand what it was like to ride it. Finnegan is a keen observer of place, nature, the local politics of surfing spots, and the geopolitics of our globalizing world. With this blend of perceptiveness about the relationship between the natural world and human society, Barbarian Days reminded me a lot of Helen MacDonald’s H is for Hawk.

1. Celeste Ng, Little Fires Everywhere (BOTM, September Selection)

Set in the liberal Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights, Ng’s story follows the spiraling events that unfold after Mia, an artist, and her daughter Pearl move to town and befriend the Richardson family. The Richardsons have lived in Shaker Heights for generations and pride themselves on exemplifying the progressive politics of the neighborhood. When Mia takes sides against the Richardson’s family friends, who have gained custody of the Chinese- American baby of Mia’s co-worker and plan to adopt her, Mrs. Richardson begins uncovering some of Mia and Pearl’s own secrets. Like Ko’s The Leavers, LaValle’s The Changeling, and Boyne’s The Heart’s Invisible Furies, Ng uses adoption, race, and place to explore the relationship between heritage and belonging, tolerance and bias, and the tension between race-blindness and liberals’ own blindness to their complicity in “othering” and discrimination. Despite these heavy-hitting themes, Little Fires Everywhere is never didactic, and, in fact, it reads like a cross between a coming-of-age novel and a crime thriller. I absolutely loved it, and one of the highlights of my year was being retweeted by Ng herself when The Metropole ran a post about race and real estate in postwar Shaker Heights.

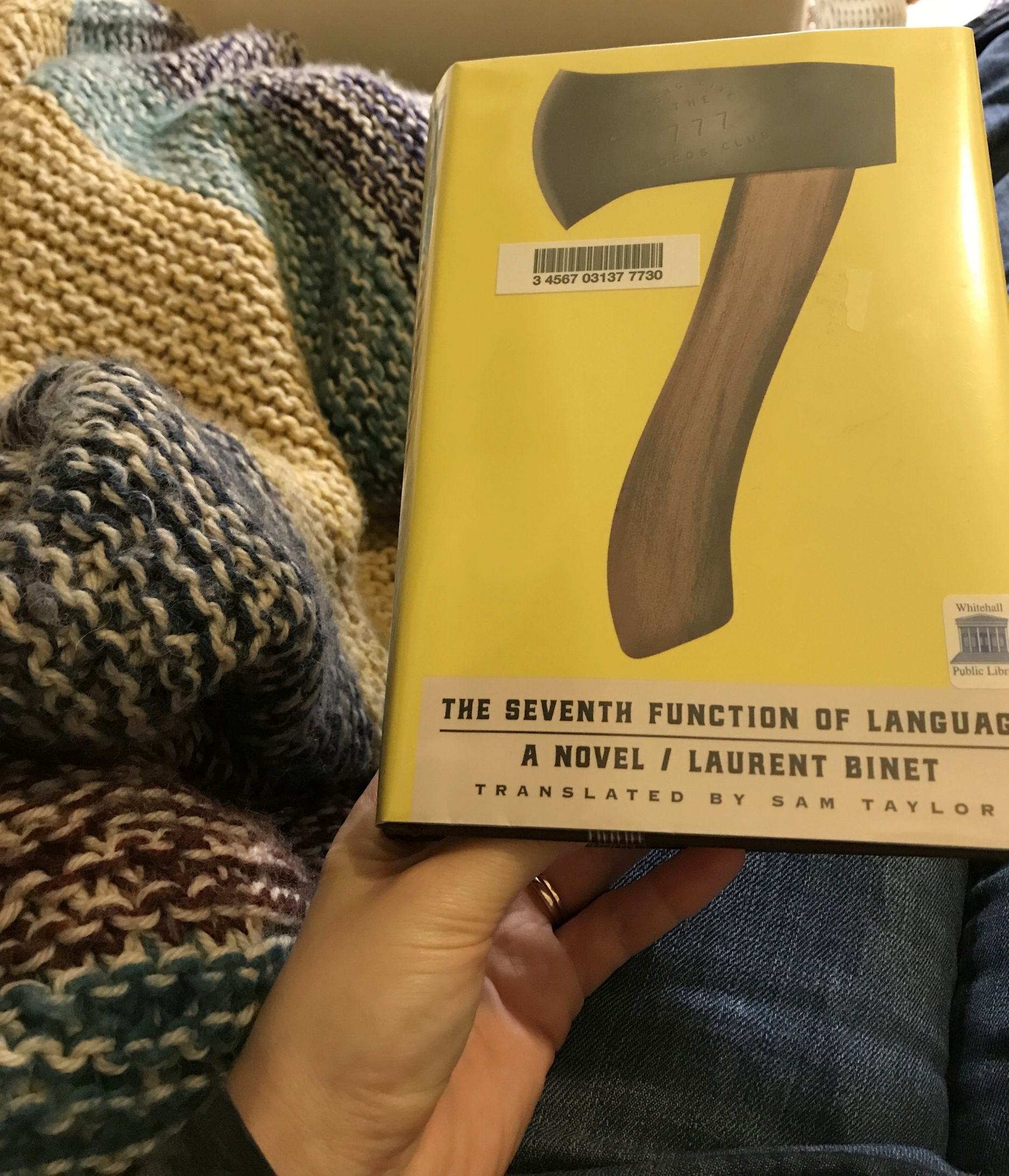

Honorable Mentions: Laurent Binet, The Seventh Function of Language; Roberto Bolaño, The Savage Detectives; Chris Hadfield, An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth. All of these were fun reads, but made less of an impression than my top ten did.

And, the bonus lists...

Kevin Seal’s Favorite Books for Young Readers Read in 2017

10. Rita Williams-Garcia, Clayton Byrd Goes Underground

9. Tom Angleberger, The Strange Case of Origami Yoda

8. Rebecca Stead, When You Reach Me [I also loved this one]

7. M.T. Anderson, Whales on Stilts

6. Casey Lyall, Howard Wallace, P.I.

5. Lisa Thompson, The Goldfish Boy

4. Lauren Wolk, Wolf Hollow

3. Dave Barry and Ridley Pearson, Peter and the Starcatchers

1. John David Anderson, Ms. Bixby’s Last Day

Amanda Katz’s Ten Favorite Reads of 2017

10. Denis Thériault, The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman

9. Anthony Doerr, All the Light We Cannot See

8. Sy Montgomery, The Soul of an Octopus

7. John Berendt, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

6. Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid's Tale

5. Nathan Hill, The Nix

4. Truman Capote, In Cold Blood

3. Sherman Alexie, You Don't Have to Say You Love Me

2. David Grann, Killers of the Flower Moon

1. Amor Towles, A Gentleman in Moscow