Yesterday I hovered my cursor over eight paragraphs of writing, highlighted them, and clicked delete. I did it swiftly, with assuredness, and I did not whine or cry. This moment represents extraordinary growth as a writer and as an adult woman. I made a painful choice with the confidence that it would ultimately yield the optimal outcome--in this case, narrative coherence.

In the year after graduating college, I started a writing group with some friends. We were all in our first jobs and missed the best parts of an academic life--debating, new ideas, critical reading and creative writing. We each had our own shtick--I churned out personal essays, another friend wrote feminist short stories, my roommate practiced magazine-style pieces--and our workshops were lively debates between prose minimalists and maximalists, sentimentalists and brutalists, realists and absurdists. If my first undergraduate seminar taught me how to write and my first graduate seminar taught me how to argue, it was this writing group that taught me how to edit my own work. My friend Sarah urged me to practice deleting. "Murder your darlings," she would say, and I would spend the next ten minutes defending the paragraph in question and justifying its inclusion in the essay. She was always right, and I would come around eventually. The paragraph would be cut and pasted into a new Word document and saved "just in case." They always stayed murdered.

Flashing back to the present, yesterday I realized that I had taken a major misstep in the current section of my dissertation. My first chapter argues that Jewish social workers used their professional credentials to keep Jewish Community Centers under their control (and out of the control of rabbis). In order to demonstrate what these credentials were and how Jewish social workers achieved them, I had decided to write a linear narrative that first explained the professionalization of social work, then the subspecialty of Jewish social work, and then the even more particular specialty of social work in Jewish Centers. I imagined it working like a funnel. First would come the most general, national part of the story. Then would come the close-up on Jewish welfare workers. Finally, the lens would narrow once more onto workers in one distinct kind of agency.

Weeks passed, I wrote several pages about social work professionalization, and then I started trying to define "Jewish social work." It forced me to go back and find exactly when this moniker was first used, and in the process of searching through old charity publications from 1900-1910 it became clear that my funnel model did not work. "Social work" and "Jewish social work" arose at the same time and were mutually constitutive. To describe a linear progression from the former to the latter was to obscure the influence that Jewish charity work had on the field as a whole. The other problem was that my chapter was supposed to focus on Jewish social workers, but I had diluted that focus by turning my attention to the Protestant evangelical "ladies bountiful" and scientific charity workers and psychiatrists who were also trying to achieve professional credentials. It turned out that I had mistaken a pyramid for a funnel. I did not actually have a tool for narrowing down something larger. I had a clunky pyramid that put the lowest common denominator at eye level and strained your neck when you tried to peer up at the nuances.

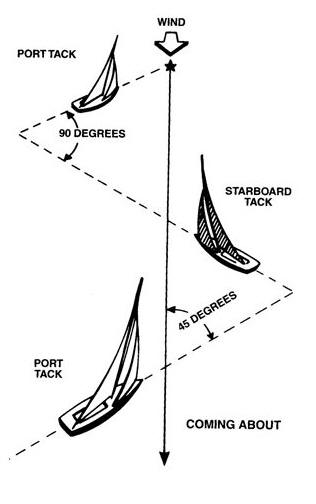

So, I did what I had to do to fix it. I muttered a blue streak that any sailor would be proud of, took a deep breath, and cut out the eight paragraphs of digression. I moved them into a new document and will use them later for an article I want to write on the topic of social work professionalization. Now I am starting to re-write this history using a sailboat as my model--I'm tacking back and forth between the specific (Jewish social work) to the general (non-sectarian social work). This leaves the focus on the Jewish workers, but provides context for their decisions and their arguments.

I told this to my friend Jessica over dinner last night, and she objected to the characterization of this process as "murder." "It's sending your words to a foster home," she said, "while you get your house in order." It's true that sometimes they stay there forever, permanently adopted by the Word document that you will never open again. More often, however, these darlings make their way back when you're ready to use them. It's not a perfect analogy--the foster care system is obviously much more traumatic for children and families than the process of writing is for authors--but it gives me the illusion that I exist in a writerly utopia where the crime rate is low and a safety net exists to help me survive a spot of trouble.